Fresh Picks

News, Thoughts & Observations

Ever-Amazing Apples

When Liberty first opened in 2013, few in America knew about cider, much less what it “ought to be.” In part because of this, two general approaches evolved in the US:

Seen here in mid-July, Bill’s red crabapples nearly tripled in size before harvest - finishing about the size of plums.

A beer-like approach, where apples are treated like a blank canvas and added flavors are the main focus. Just as (most) brewers have marginal concern about the specifics of grain, this approach allows cideries to use commodity-grade eating apples, perhaps specifying things like sugar and acidity levels, but little else.

A wine-like approach, where the flavors and characteristics of apples are treated as the primary, if not exclusive, focus.

If you’re reading this, you know we’re in the second camp. A tougher road for a business perhaps, but apples are our passion. It’s what we do.

Happily, apples are incredibly varied. Some, like Gravenstein, make for light-bodied, quaffable ciders, while others – Manchurian Crabapples, for instance – provide very intense flavors. Far from simply tasting “apple-y”, varietals may express a wide range of flavors, including tropical, stone fruit, berry, citrus or herbal notes.

But if there’s one type of apple we’re anxious to try, it’s the red-fleshed apple. These are relatively new on the scene, and even now are being bred across the globe as “the next big thing.” Most aren’t especially suitable for making cider. But some are – and some breeders, like our partner grower Bill Howell of Topcliffe Farms – are actually breeding red-fleshed varietals with cider in mind.

This fall, Bill was kind enough to share his entire crop of red-fleshed crabapples with us in exchange for helping assess their potential. But when we say “entire crop”, we’re not talking bins, bushels or even boxes. No, Bill’s first crop from his test trees added up to maybe one pound, providing around two cups of juice!

Despite being the smallest batch we’ve ever attempted, Bill’s plum-sized, deep-red apples have been impressive. Sugar levels in the juice were around 24.5 Brix, or enough to produce as much as 13.5% alcohol. Our meter measured 3.38 pH – about as tart as an average Granny Smith apple, but workable. We don’t have capacity to test tannins, but to taste, there’s plenty there. And perhaps most remarkable, the juice was deep, ruby-red – and unlike many red-fleshed apple ciders, remained so even after fermentation was complete.

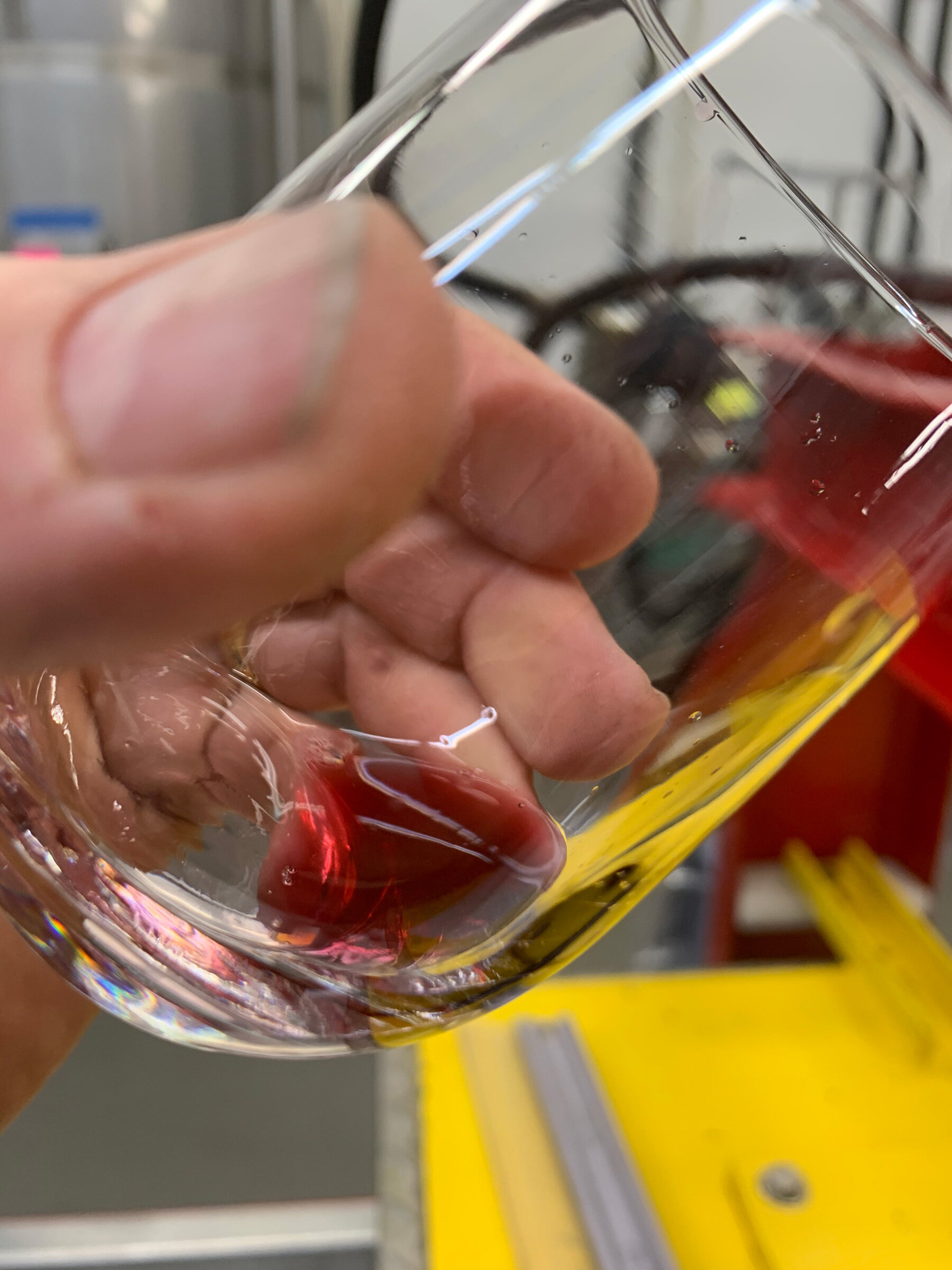

The pictures below show the apples prior to pressing, and (in tiny amounts) as immature cider. At this stage, flavors seem muted but are reminiscent of wine, almost merlot-like. We’re now letting our nano-batch rest for a while (time is always an ingredient!) to see what develops.

We’re cautiously hopeful that two or three years from now, we’ll have cider for sale made with Bill’s red apples. And that once again, we’ll be able to showcase just how versatile, flavorful and amazing apples can be.

Thanks for supporting Liberty, and stay tuned.

Holy Grail of Lost Apples

Towards the end of Apples: The Story of the Fruit of Temptation, author Frank Browning tracks noted antique apple specialist Tom Burford’s suspicions that he’d found Jefferson’s lost Taliaferro (pronounced “Taw-liver”) apple growing in the hills of Highland County Virginia.

Of the many thousands of named apple varieties lost since colonial times, the Taliaferro apple is considered the holy grail, owing to the fact that Thomas Jefferson considered them the best cider apple he’d ever experienced. Among several mentions in other writings, a letter to his granddaughter (with an enclosed cutting of scion wood) included this by Jefferson:

They are called the ‘Taliaferro’ apple, being from a seedling tree, discovered by a gentleman of that name near Williamsburg, and yield unquestionably the finest cyder we have ever known, and more like wine than any liquor I have ever tasted which was not wine.

Though Jefferson cared for close to 100 Taliaferro trees at Monticello, the original orchard is long gone. And as far as anyone knows for certain, so is the Taliaferro apple.

Burford, in correspondence with Browning, shared his story of a hillside farm belonging to a Mr. Conley Colaw where an apple matching the description of the Taliaferro still grew. And at the time (1994), Burford thought it very likely that Colaw’s apples were in fact Jefferson’s lost apple. Apples then recounts Browning’s trip to visit Colaw’s farm, where despite having missed the ability to view that year’s crop, he’s treated to a glass of cider made from the harvest, calling it “the richest, fullest-bodied farm cider I’d ever tasted, nearly dry.”

But certifying Colaw’s or any other apple as the Taliaferro may be impossible unless a more detailed, reliable description of the apple is found. Jefferson’s writings provide scant detail on their appearance or growing traits. Boston pomologist William Kenrick provided the only published description of the Taliaferro in 1835:

The fruit is the size of a grape shot, or from one to two inches in diameter; of a white color, streaked with red; with a sprightly acid, not good for the table, but apparently a very valuable cider fruit. This is understood to be a Virginia fruit, and the apple from which Mr. Jefferson's favorite cider was made.

Sadly, Mr. Burford passed away in April of this year. And other candidate apples – including some nominated by Burford as well as several others – have been proposed since Browning’s book was published in 1998.

What we do know is that the tree that grew the apples in Liberty’s 04.20 nano-batch cider came from cuttings obtained from Mr. Colaw’s tree in Highland County Virginia by (the former) Orchard Lane Growers, Gloucester VA – grafted to rootstock still growing at an orchard owned by our friend Tim Steury in Potlatch Idaho.

Tim claims the apple seems “finicky” when grown in our climate, and notes that cider made during years when the tree bears heavily is of lesser quality than years when the crop is thinner. The batch we’ve made from his trees began with small amounts of juice obtained over the course of two years, with the first batch frozen and stored for blending with juice pressed the following season.

Is this cider made with the real Taliaferro, Thomas Jefferson’s favorite apple? We’ll probably never know for sure. But it’s fun to reflect on the story, and holy grail or not, we think it’s a truly fine cider.